Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

The vast number of cholecystectomies done in the US today are done by laparoscopy, which is a technique in which the abdomen is entered with small, narrow tubes, and the abdomen is filled with carbon dioxide. Long, slender instruments are then inserted through the tubes, and the procedure is watched on a video screen. The advantage is that because the incisions in the abdominal wall are so small, there is very little pain, and recovery is quick.

Rarely, open surgery may necessary if there are unusual circumstances. These might include, for example, severe inflammation, previous surgery, or concerns about the possibility of cancer.

Your gallbladder stores bile and concentrates it between meals. When food enters the intestine, hormonal signals to the gallbladder cause the gallbladder to contract. The bile mixes with the food and helps with digestion.

How will I digest my food without my gallbladder? Do I have to change my diet?

Perhaps the gallbladder was important at a time in human history when we ate animal fats only very rarely, but it seems to be unnecessary now. Your food will digest normally without a gallbladder and you do not have to alter your diet in any way.

What are the alternatives to operation?

The only commonly accepted therapy for gallbladder disease in the United States is cholecystectomy, and most but not all cholecystectomies today are performed laparoscopically.

Breaking up the stones with shock waves as is done with kidney stones (lithotripsy) has largely disappeared due to concerns about effectiveness, recurrence of stones, and issues of cost. Medication to dissolve the stones can be taken by mouth and may dissolve a small minority of patients’ stones, but recurrence of the stones is common when the medication is stopped and the medication itself is costly.

How is the operation performed?

Usually, four small punctures are made in the abdomen. Through these very small puncture incision sites a telescope hooked to a TV cameral is introduced, along with devices such as graspers, scissors, electrocautery devices, and clip appliers. Using these, the gallbladder can be detached from the liver bed from the ducts which drain the liver, and from the blood vessels that go to the gallbladder. The gallbladder is then removed through the incision navel.

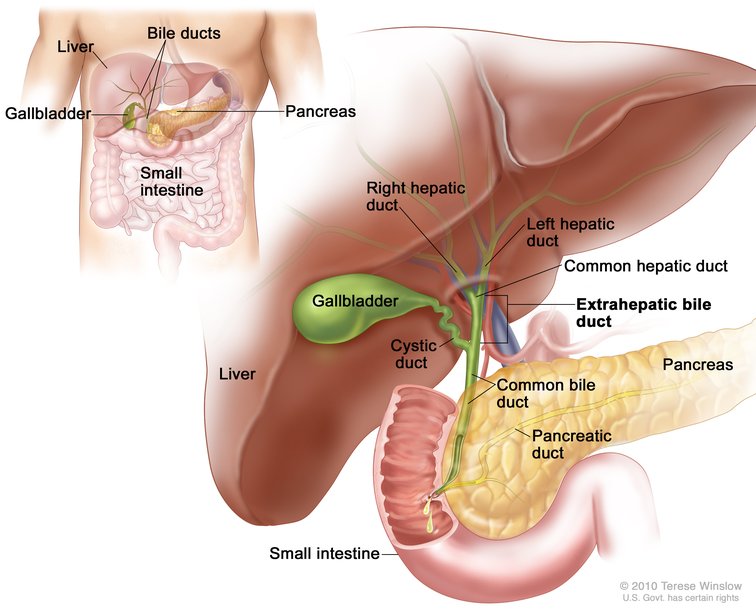

Gallbladder Anatomy

What are the risks of an operation?

Certain risks are common to all operations and include the risk of bleeding, infection, and problems related to anesthesia. Bleeding significant enough to require transfusion is very rare with these operations, and although we do not discourage you from giving your own blood in anticipation of an operation, we do not recommend it because the risk that you might need a blood transfusion is so low. Infections are extremely uncommon with these operations. Anesthetic risks relate primarily to the health of your heart and lungs — ask your anesthesiologist more about these risks, as they depend strongly on your individual health. With any major operation there is always some risk of death. This risk is generally, but not always, related to your general health and the severity of the problem for which you are undergoing surgery.

Risks unique to this procedure are primarily three:

The first is the risk of injury to the bile ducts. This can happen because of unusual anatomy or scarring from previous gallbladder attacks. Should this occur it is likely you would need a significant, open operation to repair this. Such an injury might be apparent at the time of your operation or it might not become apparent until some time later. In skilled hands this complication is rare.

The second complication is the development of a bile collection. Bile can leak from small ducts too small to be seen at the time of operation or from small leaks where the clips are used to occlude the duct where the gallbladder is attached. Some leakage of bile probably occurs commonly after these operations and causes no problems. Rarely, the leakage may be great enough that it can produce symptoms or become infected. This is usually treated by placing a drain into the collection using radiologic guidance though a small puncture in the abdomen or by using ERCP (discussed next) to decompress the bile ducts.

The third complication is that rarely, a stone may have fallen into the ducts which drain the liver and become lodged there. Postoperatively this can cause obstruction of bile drainage from the liver. Sometimes this may be suspected during the operation because we have performed X-rays that demonstrate the stone; other times it may declare itself by producing pain like that which you had before your operation or by producing jaundice — yellowing of the skin and eyes.

If a stone is recognized or suspected we will usually suggest that you undergo ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography — you can see why we use the initials) to retrieve these stones. A gastroenterologist will pass a special endoscope through your mouth into the stomach and down to where the bile duct enters the duodenum. From this site it is possible to inject dye and look for stones and it is usually possible to remove the stones as well. This procedure usually requires a stay of at most a day in the hospital, it is essentially painless, does not require a general anesthetic, and it requires essentially no recovery time. It is usually preferable to the surgical solution to this problem, which requires a significant operation, a several day stay in the hospital and considerable recovery time.

What to do before the operation . . .

- You do not need to restrict you activity in any way. If you have been having frequent attacks you may find that you will have fewer of them if you stick to a low fat diet.

- Should you have an episode of pain that lasts longer than 8-12 hours, or jaundice (your eyes and skin will turn yellow and you may notice that your urine turns dark) then you should contact the office if it is during the day, or going to the emergency room at Community Hospital. It may be safest for you to be hospitalized and your operation performed sooner than scheduled.

- For at least a week before your operation you should avoid any medications that contain aspirin or aspirin-like drugs (sometimes referred to as “nonsteroidal antiinflammatories). This includes, for example, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), Alka-selzer, Naprosyn, Ansaid, Indomethicin, and cold remedies that contain any of these drugs. All of these drugs may interfere with normal blood clotting. If you take any of these medications on the recommendation of your regular physician then be sure to ask us if it is safe to discontinue them.

Your Operation —

The night before your operation you should take nothing to eat or drink after midnight except for prescription medications. These can be taken with a swallow of liquid unless your anesthesiologist asks you not to.

On the day of your operation an IV will be placed and you will be given sedation if you need it. You will be taken to the operating room where EKG leads will be placed on your chest and all monitors will be put in place. From the time you leave the preop holding area until we are ready to begin the operation takes about 20 to 30 minutes.

Generally, the operation takes about an hour, though it can take significantly more or less time and this does not necessarily mean that anything has gone wrong. As soon as the operation is completed your surgeon will look for any family members in the waiting area. You will be in the Recovery Room for 1 1/2-3 hours after the procedure before being discharged to home or admitted overnight.

Please understand that we do our best to stick to operating schedules, but the nature of our work makes these schedules only approximations. Some operations take more or less time than expected, emergencies happen, and schedules sometimes change. We can promise you that we will not cut corners on your operation just because there are other patients waiting, and if you need emergency care you will get it when you need it — not when our elective schedule has room. Bring a book and please understand that your operation could go earlier or later than the scheduled time.

What to expect after surgery . . .

- You will have small tape strips across the puncture sites; you can shower over these and you need no other dressings. These will start to peel off on their own in a few days and you can remove them. If you have oozing from the puncture sites you should shower and apply a bandage to keep you clothes clean. This will stop on its own in a short time.

- You may eat whatever appeals to you after the operation. The old advice that you should eat a low fat diet because you have had a cholecystectomy is nonsense — you may eat just as you would otherwise. If you become constipated you may take whatever over-the-counter medications, enemas or suppositories you would normally use.

- Similarly, you may do whatever activity is comfortable to you as you feel fit. Some people take pain medication for at least a few days after their operation, and you may find that you need more rest than usual for a week or more afterward. Listen to your body — rest when you feel tired, eat what looks good to you, exercise as you feel the urge and cut back on your activity when it starts to hurt. But don’t restrict yourself just because you think you “ought “to.”

What to look for after the operation.

It is natural to feel tired for several days after the operation and to have some pain in the puncture sites. Some people will have gas pains and some minor indigestion for a few days. These are natural. If you have any of the following, however, you should call the office and ask to speak with the surgeon on call, or go to an emergency room:

- fever greater than 101 degrees

- nausea and vomiting that prevent you from keeping down fluids

- severe or worsening abdominal pain.

- yellowing of your eyes or skin.

If you have questions that are not urgent please call our office during the week, 831-649-0808.

Copyright: Mark Vierra,MD 2/8/2012